Hi lollipop! Thank you so much for all your well wishes this week. I’m still testing positive for covid but I discovered a hack to expand my radius on uber eats so that I can get hot flagels delivered so all things considered I’m doing pretty good.

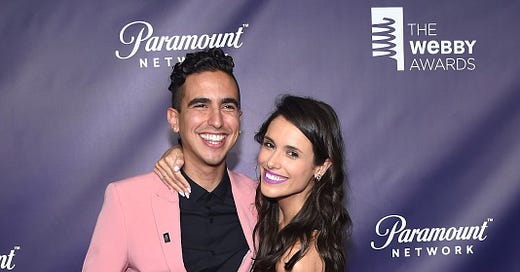

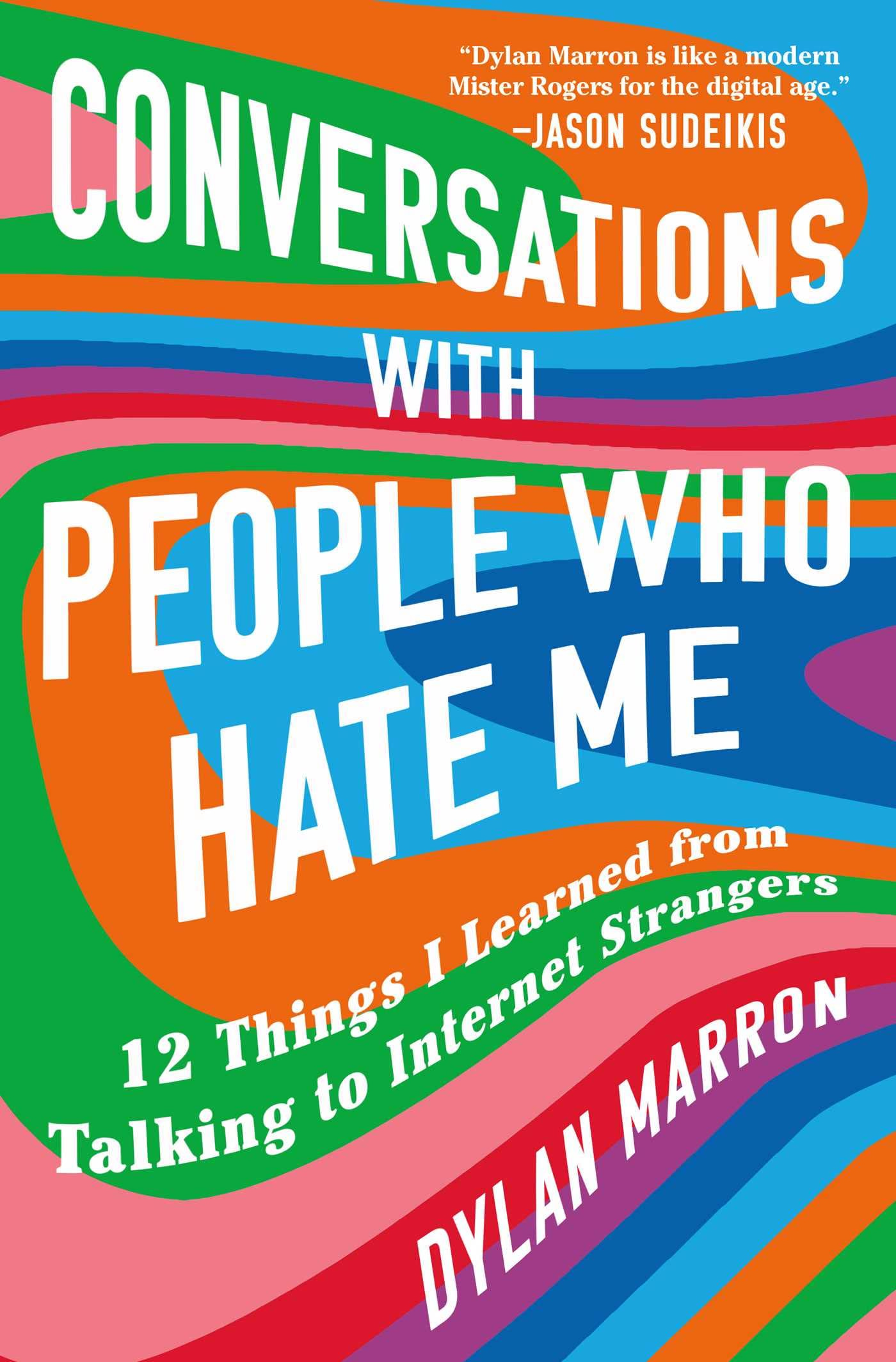

Now for our main event! What do Jason Sudeikis, Bowen Yang and Glennon Doyle all have in common? They all adore Dylan Marron’s long-awaited first book Conversations with People Who Hate Me: 12 Things I Learned from Talking to Internet Strangers. There’s so much to love about Marron, who Sudeikis refers to as nothing less than the “modern Mister Rogers for the digital age.” As you can tell from this fancy picture of the first time we met on a red carpet at the Webby Awards, I think he’s pretty spectacular too.

Marron is not just a supremely talented writer (he works on this small indie tv show you may have heard of called Ted Lasso) he has more guts than most of us combined. His book details his daring decision to take his most vicious trolls and call them up to understand them and better understand himself. He offers powerful lessons in peaceful conflict resolution that all of us can use in our daily kerfuffles with our family, friends, significant others and coworkers, something that feels very on trend right now. Marron kindly agreed to answer a few very exclusive questions just for our community. I hope you enjoy our conversation and that you get your paws on Marron’s brave and compassionate new book. You can also follow Marron on Instagram, watch his Ted Talk or listen to his podcast too.

LP: Hi Dylan! Thank you so much for writing this book and talking to us about it. What do you think is the number one mistake most people tend to make when having conversations with people who disagree with them?

Dylan Marron: There are a few but I'd say the biggest one is that we confuse conversation for debate because many of us falsely think that the only way to speak to people who disagree with us is to debate them. But I'll come out and say it: I don't think debate works. Debate is gamified conversation. It crowns a winner and loser. But what does "winning" a debate actually do? Does it change people's minds? Does it affect real change? Does it invite more people to the table? I don't think it does. I think it's a spectator sport that motivates us to sharpen our talking points more than it calls us to listen and grow.

LP: What is the most misunderstood truth about internet trolls?

Dylan Marron: Well, first of all, I don't use the word "trolls" to describe people who write mean things online anymore. And my reason for abolishing that term from my lexicon also serves as an answer to this question. The term evokes a distant "other" and lulls us into the fantasy that it's just Those People Over There—ogres under a bridge—who write mean comments to us, The Good People. But that's just not true. In my five years of doing this project, I've found over and over again that my guests are not human anomalies. They are humans, too. Which is, of course, not to suggest that the content of what they've said hasn't been offensive or hurtful. It has been. Quite often it's even been devastating. But I think when we use the word "trolls," we misunderstand negative internet comments as someone else's problem when I worry that the platforms we use to communicate enable that kind of behavior in all of us.

LP: I’ve always been fascinated by the fact that movies and most makeover shows usually feature transformations of people who are already redeemable. That’s why I love your work so much. What could the world look like if we helped those who are the least redeemable, heal?

Dylan Marron: I think everyone is redeemable—but redemption is tricky because it can only be determined by the person who has been directly hurt by the person up for redemption. Meaning: it's not my place to tell you who you should forgive. Speaking for myself, when someone who said something cruel to me online accepts my invitation to talk and they show up with vulnerability and humility, I forgive them because I consider conversation itself to be an apology.

I head into all of my conversations with this mindset, and I think that's what enables me to forge a connection with someone who I could more easily write off as an irredeemable adversary. So I think if we all took some time to really consider what we define as a "good apology"—and give people the opportunity to make them—I think that's how we move forward.

But in terms of "healing" them, I don't think that's our job. That's up to them to heal themselves if they are indeed hurt.

Internet trolls don’t just hurt the people they’re trolling, they’ve also turned into larger more threatening movements like QANON, how can people help family members who have fallen down the rabbit hole?

To be honest my specialty isn't in de-radicalization, but I will say that I have found success whenever I've separated an individual from the group they are knowingly or unknowingly part of. At the same time, conversation has its limits. While I believe in it, one conversation will not undo the harm caused by larger mobs.

LP: What gives you hope?

Dylan Marron: The guests I've met through this show. The conversations I've had with them. And the fact that even if the conversation doesn't end well, almost all of my guests feel a shift after taking part in this social experiment.

After ten days you are no longer contagious. You could feel completely better and continue to test positive for up to three months so no need to keep testing. If you’re traveling internationally or need a negative test for an event you can bring the original positive test and a certificate of recovery from your Doctor instead.

Firstly, glad you’re feeling better! Despite the diminished health, carbs are STILL not safe! I’m also now more educated about the wider world of bagels having read this newsletter. If I just smash down a bag bagel I buy in bulk from Sam’s Club, can I call that a flagel? Going to anyway. 😁 🥯 Seriously, get to 100% wellness soon. The world seems flatter without tearing up the place...